Your cart is currently empty!

Posted in

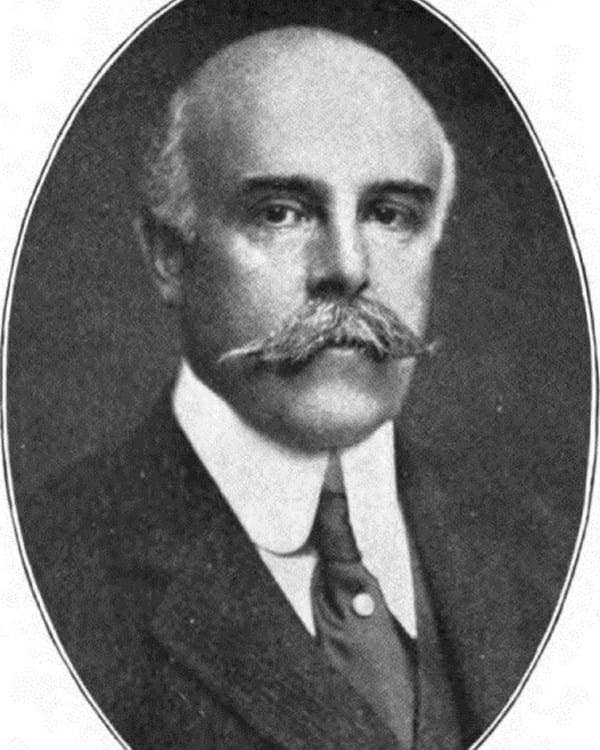

Madison Grant was a complex and influential figure whose work significantly impacted both the early conservation movement and the eugenics movement in the United States. His legacy, while often celebrated for his efforts to preserve America’s natural landscapes and wildlife, is inseparable from his deeply held and problematic beliefs in racial hierarchy, which he sought to institutionalize through his advocacy of eugenics. Grant’s writings and actions not only helped shape early environmental policies but also laid the foundation for restrictive immigration laws and exclusionary practices rooted in the pseudoscience of racial purity. His life’s work shows how the ideals of conservation were founded on eugenic ideology during the early 20th century.

One of Grant’s most significant contributions to the conservation movement was his co-founding of the Boone and Crockett Club, an influential organization dedicated to preserving wildlife, promoting sustainable hunting practices, and establishing national parks and protected areas. Through this organization, Grant worked to secure protections for species like the American bison and elk, and in the creation of national parks such as Glacier National Park. His passion for preserving the natural environment, however, was driven by more than a simple appreciation for nature. Grant viewed conservation as a way to protect what he considered to be the superior elements of both the natural world and human society. His desire to preserve America’s wilderness was directly linked to his belief in protecting what he saw as the purity of the American race, particularly the Nordic race, which he considered superior.

The Passing of a Great Race

Grant’s eugenic beliefs were clearly articulated in his 1916 book, The Passing of the Great Race, which argued for the preservation of the Nordic race and warned against the dangers of racial mixing and immigration. In this book, Grant outlined a vision of America where racial purity was paramount, and he promoted the idea that the influx of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, as well as the presence of Native Americans and African Americans, posed a threat to the nation’s racial integrity. This racial purity, in Grant’s view, was as important to the survival of the nation as the conservation of its natural resources. He believed that both the land and the people needed to be protected from degradation, and he saw eugenics as a scientific method to achieve this goal.

Grant’s influence on American policy was profound. He was a major advocate for the Immigration Act of 1924, which implemented strict racial quotas designed to limit the immigration of people from regions Grant deemed racially inferior. This legislation was directly inspired by the ideas Grant laid out in The Passing of the Great Race, reflecting his belief that the nation’s demographics needed to be controlled to maintain its racial character. In this way, Grant’s conservation efforts and his eugenics advocacy were part of the same overarching goal: to safeguard the nation’s resources, both natural and human, from perceived threats.

Grant’s racial ideas did not stop at immigration policy. He also viewed Native Americans and other non-white populations as threats to the Nordic race. He advocated for the confinement and, in some cases, the extermination of Native American tribes, seeing their presence as detrimental to both the racial and environmental purity of the country. In this respect, Grant’s vision of conservation extended to managing not only wildlife but also human populations, in ways that reflected the hierarchical racial order he believed in. For Grant, the preservation of the nation’s landscapes and the preservation of its racial identity were inextricably linked.

Madison Grant’s influence extended far beyond the borders of the United States. His writings, particularly The Passing of the Great Race, had a profound impact on global racial ideologies, including those of Adolf Hitler. Hitler himself praised Grant’s work, referring to it as his “bible,” and the racial purity laws implemented by the Nazi regime in Germany were heavily influenced by Grant’s ideas. The horrific consequences of these policies during the Holocaust highlight the dangerous and far-reaching effects of the eugenicist ideas that Grant and others promoted.

While Madison Grant is often remembered for his contributions to the conservation of America’s natural landscapes, it is essential to recognize the darker side of his legacy. His environmentalism was deeply intertwined with his eugenicist beliefs, and the organizations he helped found, such as the Boone and Crockett Club and the American Eugenics Society, reflect this intersection. The early conservation movement in the United States, as exemplified by Grant’s work, was not solely about preserving nature for future generations but also about preserving a particular racial and social order.

Nazi Regime and the Implementation of Grant’s Conservation Ideals

The National Socialist German Workers’ Party (in German, Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, or NSDAP), heavily influenced by ideas of racial purity and nationalist ideology, embraced Madison Grant’s philosophy of conservation as an integral part of their broader social and political goals. The Nazis saw the protection of the environment as a means of safeguarding the “purity” of the Aryan race and reinforcing their connection to the land. This perspective mirrored those of Madison Grant, which sought to control both the human population and the natural landscape.

Adolf Hitler and several Nazi leaders admired Grant’s work, particularly his book The Passing of the Great Race, which promoted racial hierarchies and the idea of protecting the “Nordic” race from degeneration. As a result, Nazi environmental policies were designed to align with their racial ideology, and they implemented sweeping conservation reforms to protect the German landscape. Laws were passed to regulate forestry, protect wildlife, and preserve natural spaces, bringing Germans “closer to nature” in a way that reinforced national identity and racial purity.

The Nazi regime created the Reich Conservation Law in 1935, which placed significant restrictions on land use and promoted large-scale forest conservation and sustainable agriculture. However, these policies were not purely environmental. They were part of the Nazi vision of Lebensraum (“living space”), a concept that justified territorial expansion and the displacement of millions of people. While these environmental initiatives appeared to be progressive on the surface, they were deeply rooted in the same exclusionary and supremacist ideology that inspired their genocidal actions.

Grant’s influence, therefore, went beyond American conservation and directly contributed to the environmental policies of the Third Reich. By romanticizing nature and the Aryan race’s relationship to it, the Nazis used conservation as another tool to further their agenda, showing that environmental goals are directly linked to dangerous ideologies and supremacist views.

The connection between nature conservation and Nazi ideology cannot be ignored.

The conservation movement in the United States of America is rooted in some of the most atrocious genocidal acts ever committed against humanity. Madison Grant’s legacy is contradictory to the labels and insults often hurled toward those defending land-use rights. In reality, whether knowingly or unknowingly, those who fight for overreaching restrictions on land use are aligning themselves with a dangerous belief system that goes far beyond the environment.

Grant’s belief that the Nordic race needed to be protected from perceived threats, both human and environmental, shaped conservation policy in the United States and influenced policies that had devastating consequences for millions of people around the world. His work reminds us who the real Nazis are.

Tags:

You may also like…

Visit the AZBackroads.com Store

Please Become A Member

We need your help to keep our backroads open. Please join today!